Dr Anthony Mann is a Senior Policy Analyst in the OECD's Education and Skills Directorate.

Dr Anthony Mann is a Senior Policy Analyst in the OECD's Education and Skills Directorate.He is a former policy official in the UK government and an expert in youth employment, VET and career guidance for more than 20 years. Mann is lead author of the OECD report Dream Jobs? Teenagers' Career Aspirations and the Future of Work (2020); the Investing in Career Guidance (2019) leaflet jointly published by Cedefop, European Commission, European Training Foundation, OECD and UNESCO; and Career Ready? How schools can better prepare young people for working life in the era of COVID-19 (published on 15 December 2020).

During 2021, Anthony is leading new work which will develop tools for school to measure the career readiness of young people. To find out more and to stay in touch with the work, email him at Anthony.Mann@oecd.org stating if you prefer updates in Spanish and/or follow him on twitter @AnthonyMannOECD.

What career guidance goals would you recommend prioritizing in a job crisis like the one we are living because the COVID-19 pandemic?

Never before in human history has career guidance been more important. Even before the pandemic, the need was clear. As young people stay in education longer, they make ever more decisions, but the increasing dynamism of the labour market, the rapidly changing demand for skills and the growing diversification of education and training provision has made decision-making more difficult. Now with Covid-19, we see a healthcare catastrophe create a jobs crisis for young people.

For guidance professionals, the challenge is to help young people go into the labour market ready to launch their careers. Young people are always at an inherent disadvantage in the competition for work because they know less about work, have fewer useful contacts and less experience to draw upon. In a recession, such disadvantage is amplified.

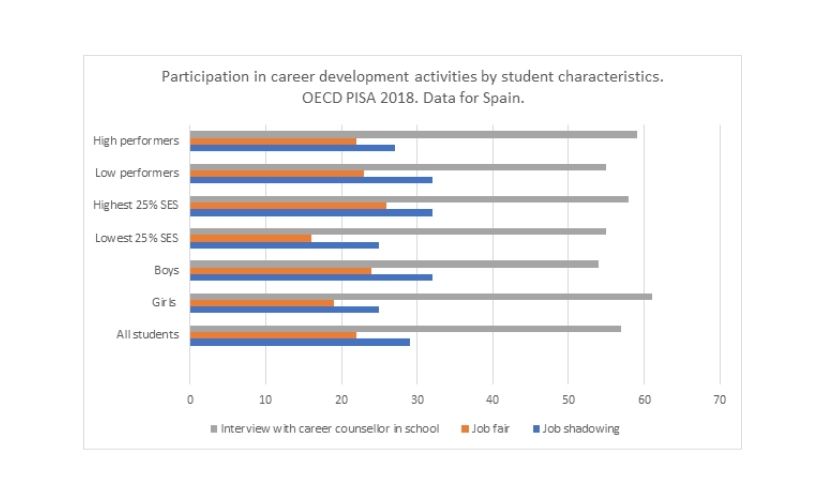

OECD data suggests that there is significant room for concern over the likely career readiness of the generation of students now leaving secondary education. The 2018 PISA survey was conducted with hundreds of thousands of 15-year-old students around the world. It found that across the OECD only half had seen a guidance counsellor in school by this age and less than 40% attended a job fair or been on a workplace visit. PISA shows that student thinking about the labour market can be characterised as narrow, confused and distorted by social background. In most countries, evidence of effective signalling from the labour market is weak and the need for young people to have access to greater levels of guidance is clear. In selected Latin countries, PISA demonstrates participation levels commonly below OECD averages.

Effective youth guidance will be based on evidence of its long-term impact. New analysis of national longitudinal datasets by the OECD shows that young people do better than expected in the adult labour market if, as teenagers, they demonstrate agency and engagement in their school-to-work transition across three broad areas. Students can be expected to do better in the adult employment if they show that as teenagers they are:

- Thinking about their future working lives,

- Exploring potential careers through conversations and career development activities

- Gaining first-hand experience of the workplace through placements, part-time working or volunteering.

For schools, data-driven guidance will provide confidence that young people are on track to compete as well as can be expected for available employment. Consequently, a priority is to provide students with multiple opportunities to engage with, and reflect on, authentic experiences of work and people in employment. In that way, young people are helped to critically reflect on their own individual relationship between the education and training choices they make and anticipated futures in work. For schools it is not enough to enable such provision, young people also need to be challenged and supported to reflect on their assumptions, interests, and abilities considering what they learn about the dynamic labour market.

And what do you think are the three main challenges of career guidance to face the job crisis that the pandemic is leaving?

In a recessionary climate, it is more important than ever to go back to basics and ensure that the disadvantages that prevent young people from competing well in the labour market are addressed. Career ready students will have a good understanding of the world of work and informed views about how they expect to participate within it, they will have actively explored their career interests through multiple discussions with guidance professionals and people in work, and they will have been required to gain first-hand experiences of the workplace.

For career guidance, the challenge has been how to enable such development during a time of lockdowns and social distancing. In many countries, alternative provision has stepped in. We see personal guidance, job fairs, career talks and interview workshops all being delivered online. Here, it is important to keep in mind what makes such provision most effective in face-to-face delivery. Above all, students need to have confidence that the information and advice they are receiving is authentic. In general, guidance should be compulsory, and students encouraged and enabled to prepare thoroughly in advance of interventions and reflect on experiences afterwards. An excellent question to ask students after a career exploration event is whether it was useful to them. Longitudinal studies show that students who find sessions very helpful as teenagers typically go on to do better in work as young adults. We need to be aware that young people will bring their own assumptions and prejudices into career thinking and encourage them to broaden their aspirations.

A notably difficult challenge has been accessing to workplace experience. Work placements have been ground to halt. In some countries, experiments have been undertaken with online placements and a priority should be to review these quickly and transparently. In work-based learning, within programmes of Vocational Education and Training, the need for placements to resume is particularly urgent. The OECD has gathered examples of work-arounds that readers may find useful in VET in a time of crisis.

"It is important that countries encourage and enable schools to ensure that young people from the most disadvantaged backgrounds have easy and plentiful access to guidance".

What career guidance strategies, actions or practices do you think should be carried out mainly to face the challenges you mentioned?

In this crisis, there is an urgent need sure that provision is as effective as possible – which is to say, that it is based around indicators of better outcomes in adult employment. Data-driven guidance presents practitioners with indicators that collectively provide confidence that young people are on track to compete as well as expected in the labour market. For example, studies show that 15-year-olds who cannot name a job they expect to do at age 30 or who underestimate the level of education required to secure a job ambition typically do worse than comparable peers in work. We can identify too in national literature examples of indicators related to career exploration and workplace experience whether it be part-time working, work placements or volunteering.

The new OECD working paper, Career Ready? How schools can better prepare young people for working life in the era of COVID-19 sets out what is currently known about such indicators and launches a 12-month project designed to provide working tools for governments and schools interested in testing the effectiveness of programmes and assessing the career readiness of students.

Among the groups most affected by the pandemic in economic and employment terms, young people (even those who are trained) and people without studies or training. What could be done from career guidance to improve their opportunities?

Breaking down the 2018 PISA data for Spain, we see that participation in important career development activities is patterned by socio-economic status (SES), academic performance and gender. It is a matter of concern that young people from the most disadvantaged social backgrounds and with the lowest levels of academic performance can often expect to experience lower levels of guidance than their more advantaged peers. They should be getting the most provision. International research consistently shows that it is young people from the most disadvantaged backgrounds who have the greatest need for guidance.

It is important that countries encourage and enable schools to ensure that young people from the most disadvantaged backgrounds have easy and plentiful access to guidance. International evidence shows that where young people are well prepared for their working lives, they do better than would be anticipated given their backgrounds. Education systems and schools have an essential role to play in levelling the playing field and democratising access to the information, experiences and support that make a difference in school to work transitions. This begins by tracking participation levels and acting if evidence emerges that disadvantage in life is compounded by disadvantage in access to guidance.

Can you tell us about good career guidance practices that have been or are being carried out during the pandemic in Europe?

Very soon, Cedefop will publish the results of a global survey of people working in career guidance and policy. The survey was undertaken in the spring of 2020 and explores in part how the delivery of guidance was adapted to the restrictions caused by the pandemic. In most countries, action was taken quickly to deliver face-to-face guidance through alternative means. Counselling sessions were delivered through video links or over the telephone. Guidance was made available on video sharing websites and in many countries, we saw online job fairs and virtual open days at post-secondary education institutions. Perhaps the most ambitious response was the Oak National Academy in England where many new online resources were made available to thousands of schools through a national organisation. These included online lessons with high profile employers designed to replace work experience placements typically undertaken by 15-year-olds.

Surely the experience we are living, and its impact can serve to correct guidance practices that allow us to reinforce aspects that we have neglected until now. Could you tell us an example?

Vocational Education and Training (VET) provides an excellent example. Where VET provision is of high quality and fully engages employers, students can have confidence that programmes will be a gateway to skilled employment. However, PISA tells us that in many countries, young people's interest in VET is sharply constrained by their social backgrounds. In too many countries, VET is perceived as something for low achieving, native-born boys of lower socio-economic status. In a recession, it is more important than ever that the widest range of young people have opportunity to consider VET programmes. We saw in the Great Financial Crisis of 2007/08, that youth employment was maintained in countries with strong VET systems like Germany and Switzerland. Here, strong employer involvement ensured that VET programmes provided students with confidence that their training programme would lead to good work. Since 2008, many countries have reformed their VET systems to make them more attractive, but PISA 2018 tells us that this message is not getting through to many young people.

New Zealand provides a good example of a country that is intervening to increase awareness of what VET has to offer. In New Zealand, extensive skill shortages in the skilled trades are projected. In response, the government has recently announced a national marketing campaign underpinned by new funding to enable schools to run events with apprentices and apprentice employers. Volunteers will be brought into contact with students who will be given new opportunity to explore potential careers through first-hand interactions. In so doing, schools are giving young people access to trusted information that will help them to make more informed decisions as they plan their futures. Good guidance broadens aspirations and does so in part by providing young people with compelling visions of their possible working lives.